June 6, 1944, D-Day — marks one of the most pivotal days in world history.

We’ve created a short video to honor their bravery and sacrifice. Please take a moment to watch—and share it with others, especially young people.

D-Day: The Beginning of the End of World War II

The Unlikely English Professor

It was an unlikely task for an English major from Oskaloosa, Iowa, guiding other vessels to the beaches of Normandy on D-Day, 1944. But Lieutenant Junior Grade Howard Vander Beek, his 14-member crew and a 48-star American flag rose to an occasion none were expecting.

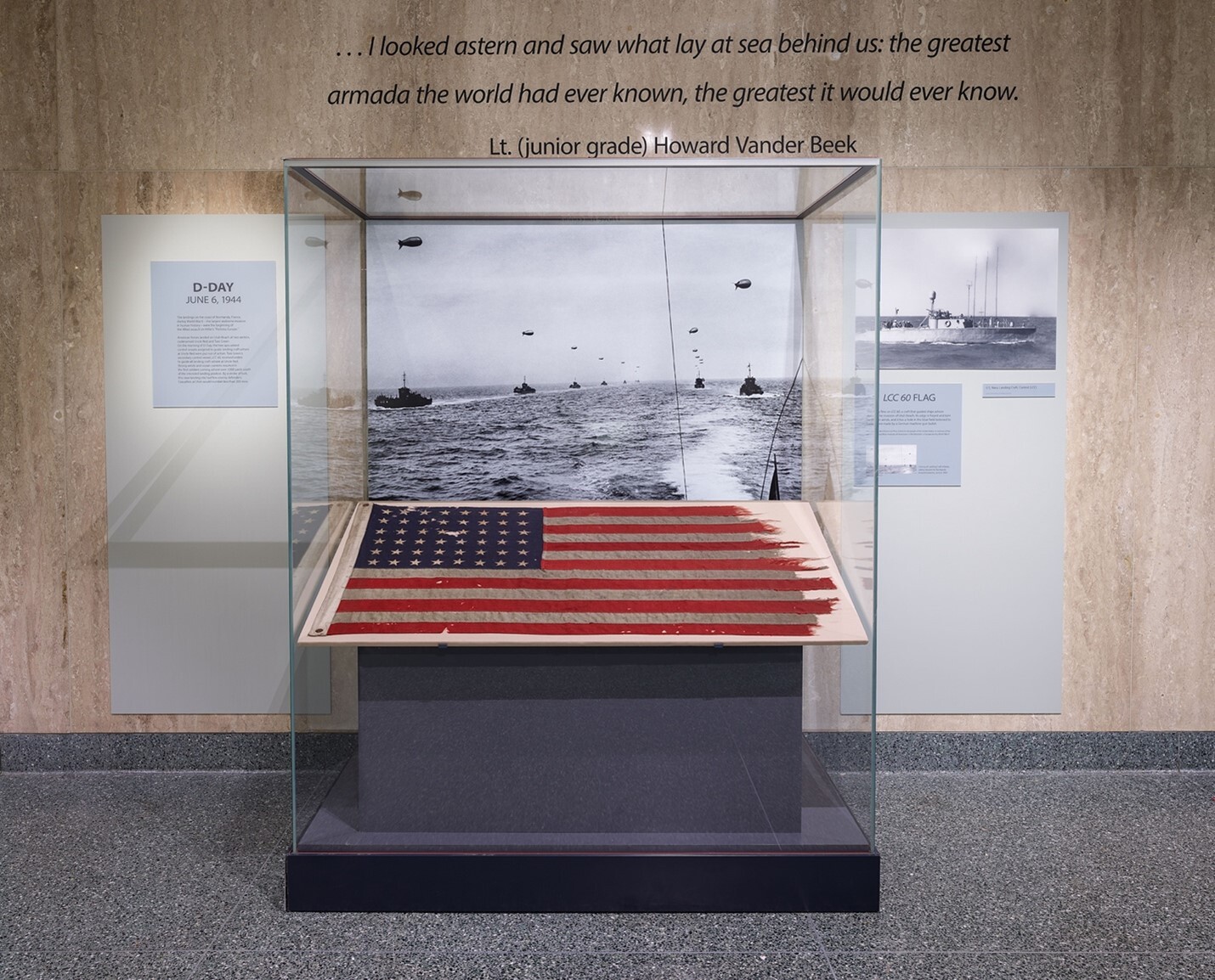

Vander Beek was captaining a specialized ship known as “Landing Craft, Control 60” or simply “LCC 60.” It was a 56-foot tin can stuffed to the gunwales with radar, radio transmitters, direction finders, underwater sound equipment and few creature comforts save a 48-star American flag flying astern. LCC 60’s job was to guide other craft safely to Utah Beach through high winds, heavy seas, poor visibility, the sound of enemy shellfire overhead and the constant threat of deadly enemy sea mines below the surface.

Vander Beek and crew were to guide landing craft to a sector of Utah Beach known as “Tare Green.” Suddenly, the primary control vessel for another sector, “Uncle Red” struck a mine and sank. When yet another vessel fouled its propeller on a buoy line, Vander Beek found himself shepherding all the invading ships to shore for both “Uncle Red” and “Tare Green” sectors.

Dangling participles, subject-verb agreements and run-on sentences were of no concern at that moment for the Iowa-born, one-day-to-be English professor.

A second world war was on. This was D-Day, a day that would change the course of both the war and the world.

The Flags of D-Day

Vander Beek and crew were essentially the point-men, guiding what Vander Beek later dubbed “the greatest armada the world has ever known, the greatest it would ever know” to victory.

A 48-star flag American flew with him all the way to Normandy, and later to another invasion of Southern France, Operation Dragoon. Vander Beek would keep the flag all his life. In his memoir he recalled the flags of D-Day, writing “Flashes of color lifted our spirits, particularly those of the American flag waving majestically over the beach. Knowing that it had been raised by men whom we had led in the assault fed our pride.”

48-star American flag that flew astern LCC 60 on D-Day

Courtesy: Smithsonian Institute

Today, the flag that flew with Vander Beek on both the northern and southern coasts of France is on display at the Smithsonian Institute in Washington, D.C.

One of Thousands and Five Beaches

Vander Beek’s story is but one of thousands of D-Day stories, chiseled from bullets and blood into stone on June 6th and succeeding days in 1944 Normandy. The 50 miles of beaches, code-named Utah, Omaha, Gold, Juno and Sword are still remembered.

Storming the beaches of Normandy on D-Day, June 6, 1944

Courtesy: U.S. National Archives

The Normandy coast was the site of Operation Overlord, the largest air, land and sea invasion in history. One-hundred fifty-six thousand Allied Forces stormed the beaches. By nightfall, 10,300 casualties. Omaha Beach alone suffered 4,000 casualties, earning the name “Bloody Omaha.”

Walking along the coastline today you can still see remnants of the war so many gave their lives for. You can peer through barbed wire overlooking the cliffs above the beaches where Allied Forces landed, then ran, crawled and clawed their way ever onward toward the enemy.

You can pause at the jagged remains of heavily fortified German gun casements that reigned death down upon brave American, British, Canadian and Free French forces. “Always take the high ground” is a universal military strategy. Allied Forces didn’t have it. Despite that, they used the element of surprise and overwhelming force to free France and the world, though at terrible cost.

The Cost of Freedom

The heavy cost of freedom is memorialized today on hallowed grounds at the Normandy American Cemetery. The remains of nearly 9,400 Americans who died during the Allied liberation of France are preserved on a high bluff overlooking the beaches where many of them perished.

Some of nearly 9,400 headstones marking the graves of Americans who gave their lives during the invasion of Normandy.

Photo: Thomas D’Amico

The remains include three Medal of Honor recipients. Forty-five sets of brothers lie side-by-side

Another 1,600 names are found on the Walls of the Missing.

In all, the cemetery and memorial comprise a 173-acre tribute to American lives lost. It is one of the best-known memorials to World War II dead, and the most visited memorial operated by the American Battle Monuments Commission. Every year, more than one million visitors arrive to pay their respects and learn more about what happened here.

One of the many visitors has been American Flags Express president Thomas D’Amico, whose words reflect the feelings of many:

“I felt a quiet reverence visiting the beaches of Normandy in November 2024... Standing where so many brave soldiers gave their lives was profoundly humbling—a powerful reminder of the immense sacrifice made in the name of freedom.”

The Normandy American Cemetery

A visitor’s center marks the entrance to Normandy American Cemetery, where visitors can view descriptions of the events of the D-Day landings and their significance to the campaign for Normandy.

Beyond the visitor center the dominant structure of the memorial is a semi-circular row of evenly spaced columns (colonnade) with a centerpiece bronze statue “Spirit of American Youth Rising from the Waves.” The statue represents the courage, sacrifice and youth of American soldiers in World War II. Although no single authoritative source has been found, multiple credible sources often list the average age of a soldier involved in D-Day as 26. Other popular sources cite 22 years, perhaps not coincidentally the same number in feet as the height of the statute. Regardless, all were too young to die or go missing, and all are remembered.

A quiet reflecting pool connects the colonnade and cemetery proper, where row-on-row of white headstones stand.

Today, American and French flags fly proudly above the graves. They flank both the reflecting pool and a small chapel roughly centered amidst the graves.

One More American Flag

Thirty-seven hundred miles across the Atlantic another American flag has been laid to rest. The 30-by-57 inch, 48-star Stars and Stripes that flew from the stern of the Landing Craft, Control 60 on D-Day is memorialized at the Smithsonian Institute in Washington, D.C. It is tattered and torn, stained by diesel exhaust and has a round hole in the field of blue believed to be caused by German machine-gun fire. It had been safeguarded by Howard Vander Beek all those years, until his death 70 years later.

This flag and Normandy American Cemetery are enduring symbols. They are reminders of the ultimate sacrifices made on the beaches of Normandy in June,1944, when thousands of U.S., British, Canadian and Free French forces crossed the English Channel to start the beginning of the end of World War II, on a day known as D-Day.